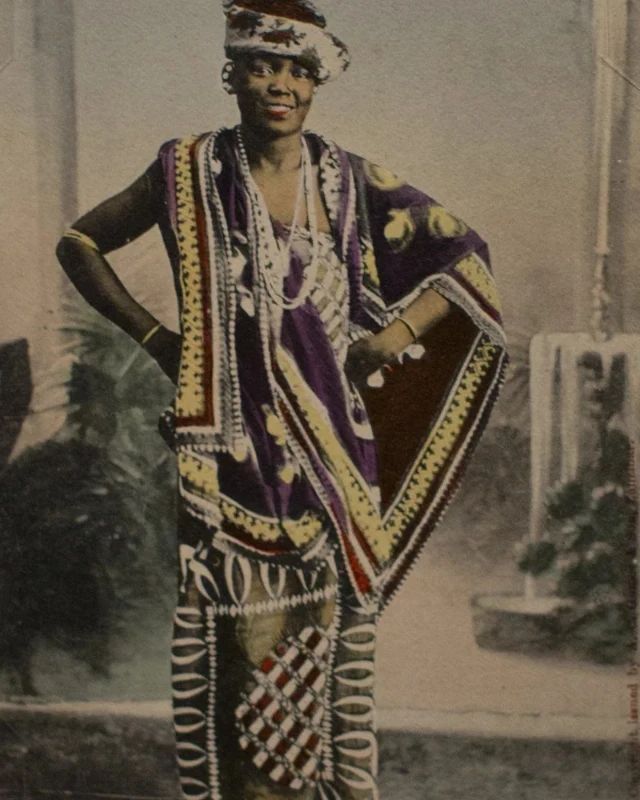

The vintage Swahili Postcards collection predominantly features photographs of women adorned in extravagant attire and jewellery, their expressions ranging from serious to playful or romantic. Many of these images have been skillfully colourized, with meticulous hand-painting bringing vivid life to ruby lips, golden pendants, and emerald chairs.

Some of the most captivating portraits were captured between the late 1890s and 1920s in studios spread across Kenya, Tanzania, and Somalia. Providing glimpses into the lives of the subjects, these images possess an extraordinary history. Unbeknownst to the individuals depicted, photographers often repurposed the negatives from private sessions and transformed them into postcards, marketed to Westerners as souvenirs from their East African travels.

These historical postcards are also showcased in a new exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C., titled “World on the Horizon: Swahili Arts Across the Indian Ocean.” presenting more than 150 objects sourced from museums and private collections across four continents, highlighting the culture and art of the Swahili coast in East Africa.

Running until September 3, the exhibition was curated by Prita Meier, who carefully selected these postcards for their ability to demonstrate the captivating and remarkable ways in which the people residing along the Swahili coast wholeheartedly embraced photography, particularly in the form of portraits and made it an integral part of their artistic expression.

Meier, an assistant professor of art history at New York University, also authorizes an upcoming book focused on photography along the Swahili coast from the 1870s to the 1970s.

According to Professor Meier, this photo, captured in East Africa in the late 1860s, quickly led to studios in cities such as Mombasa (now in Kenya) and Zanzibar’s Old Town. Soon, individuals from diverse backgrounds flocked to these studios to have their portraits taken by local photographers in intimate settings.

As Meier explains, these portraits encompass a tempting array of poses, with subjects engaging with the camera in playful, seductive, or serious manners. Most individuals donned their finest attire for these photographs. In contrast, others embraced the opportunity to adopt alternative personas and identities, masquerading as Victorian ladies, movie stars, or women in Middle Eastern harems.

Meier challenges the prevailing notion that African photography was always severe and solely aimed at expressing an essential aspect of identity. She remarked that she still wonders that fact about Africans do their photography.

During the period encompassing the exhibition’s postcard photographs (1890-1920), portrait sittings had become a popular and affordable pastime. It offered a delightful way to spend time with friends and family, akin to the photo booths in malls or the vintage dress-up studios in seaside towns.