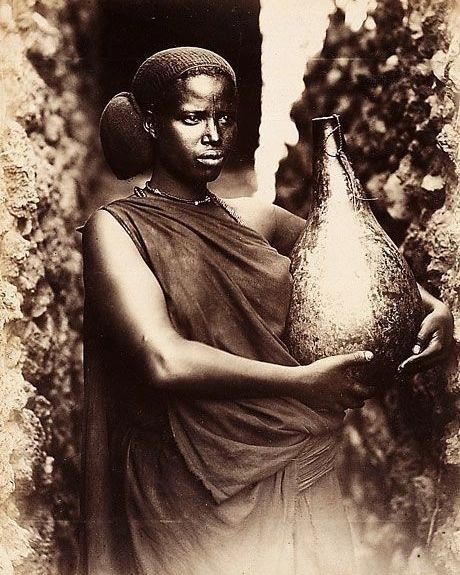

The Somali Bantu people are an ethnic group with a distinct cultural heritage and history within the broader Somali population. They are descendants of Bantu-speaking communities who migrated from various regions of East Africa to the coastal areas of Somalia centuries ago.

The origins of the Somali Bantu can be traced back to different Bantu-speaking communities, such as the Shabeelle, Juba, and Benadir Bantu groups. These communities brought rich traditions, languages, agricultural practices, and cultural customs that influenced their unique identity.

Historically, the Somali Bantu can be divided into three distinct groups. The first group comprises those indigenous to Somalia, having inhabited the region for generations. The second group consists of individuals brought to Somalia as enslaved people but eventually integrated into Somali society. The third group includes those brought to Somalia as enslaved in the 19th century but retained their ancestral culture, languages, and a distinct Southeast African identity. Unfortunately, this last group of Bantu refugees has faced persecution in Somalia.

Long before the Galla advance, the fact is that they found the Northeast Coastal Bantu already firmly settled in and cultivating the valleys of the Tana, Juba, and Shebelle Rivers and the arable land between them, but modern-day Somalia history tends to overlook this fact of the existence of indigenous Bantus.

Medieval Arabic sources, indeed, indicate that the Bantu had entered into symbiotic relationships with the indigenous hunters of the bush country before the arrival of the Galla, which can be tentatively dated at about A.D. 1000. Like the Somali, the Galla reduced the Bantu in part to dependent status. However, they intermarried with them more, and many Bantu fled southwestward into Kenya.

The Gosha and Shebelle tribes of Somalia constitute surviving pockets of comparatively unmixed Negroes, who are still basically agricultural though they have recently exchanged their original Bantu language for Cushitic.

The Somali Bantu’s distinct physical features, language dialects, and cultural practices set them apart from other Somali communities. However, these differences have often excluded them and limited access to political, economic, and educational opportunities. Many Somali Bantu have historically come from agricultural backgrounds and faced challenges such as a lack of infrastructure, including running water, electricity, and material possessions.

Following the Somali civil war in 1991, the Somali Bantu faced increased attacks from bandits and militias, as they lacked the protection of traditional Somali clan networks. As a result, many Bantu individuals fled to refugee camps in Kenya’s Northeastern province. At its peak, these camps, managed by the UNHCR, housed over 160,000 Somali Bantu refugees. Despite unsuccessful resettlement attempts in Tanzania and Mozambique, the United States recognized the group as “persecuted” and eligible for resettlement in 1999. However, due to insecurity and violence in the Kenyan refugee camp, the process of immigration to the United States was slow.

While the Somali Bantu are known for their resourcefulness, skills, and aspirations to improve their children’s lives, they require specific understanding and attention from healthcare providers. Their history of subjection in Somalia and the prevalence of violence in the refugee camps have impacted their well-being. In particular, women within the Somali Bantu community face heightened vulnerability and are at risk of sexual violence within the camps.

The Somali Bantu’s pre-migration experiences, life in refugee camps, and subsequent resettlement have contributed to significant health burdens. Their access to healthcare services in the United States must address long-term psychological and physical suffering resulting from their unique life patterns—cultural differences between Somali Bantu practices and Western norms present challenges in healthcare delivery and social services.