Switzerland-based author Felix Thürlemann was a Swiss art historian and an honourable professor of art at the University of Konstanz. French language and literature, Latin and Medieval Latin literature at the Universities of Zurich and Besançon and at the École pratique des hautes études in Paris. He also received his doctorate with a thesis on Gregory of Tours in 1973; Thurlemann, in his captivating book, “The Harem Window” (Das Haremsfenster), is an art historian who efficiently delves deep into the world of nineteenth-century Egyptian photography.

Focusing on the works of foreign photographers residing in Egypt, Thürlemann explores how these images were tailored to appeal to the growing number of European and American tourists visiting the country. The book showcases a stunning collection of photographs, including those from the Ken and Jenny Jacobson Orientalist Photograph Collection at the Getty Research Institute and the Getty Museum collection.

Thürlemann, a professor at the University of Konstanz, Germany, sheds light on the significance of the mashrabiyah, a traditional Egyptian window screen, which features prominently in these intriguing and visually captivating pictures.

Thürlemann’s interest in Orientalist photography, particularly the Egyptian variety, was sparked by encountering original prints in his colleague Bernd Stiegler’s collection at the University of Konstanz. This led him to delve into exhibition catalogues and illustrated books on the subject, where he encountered the names of renowned photographers such as the Zangaki Brothers, Félix Bonfils, Emile Bechard, Antonio Beato, Luigi Fiorillo, Pascal Sébah, and Otto Schoefft.

Curiosity drove Thürlemann to conduct further research online, where he stumbled upon a treasure trove of images. These captivating photographs offered glimpses into a distant world, showcasing pharaonic monuments along the Nile, scenes of Nile crocodile hunters, and the everyday lives of Egyptian working people from 150 years ago. The sepia-toned vintage prints, adorned with gold, exuded a special allure that captivated Thürlemann.

Each click on a thumbnail from his Google searches led him to various destinations, including anonymous eBay sellers and museum collections housing extensive Orientalist photograph archives. One significant collection that Thürlemann frequented was the Ken and Jenny Jacobson Orientalist Photograph Collection at the Getty Research Institute.

This meticulously curated anthology, assembled by the esteemed specialist Ken Jacobson, offered free access to high-quality images and reliable information. Thürlemann highlights the immense effort put into digitizing and cataloguing these photographs by scholars dedicated to the field.

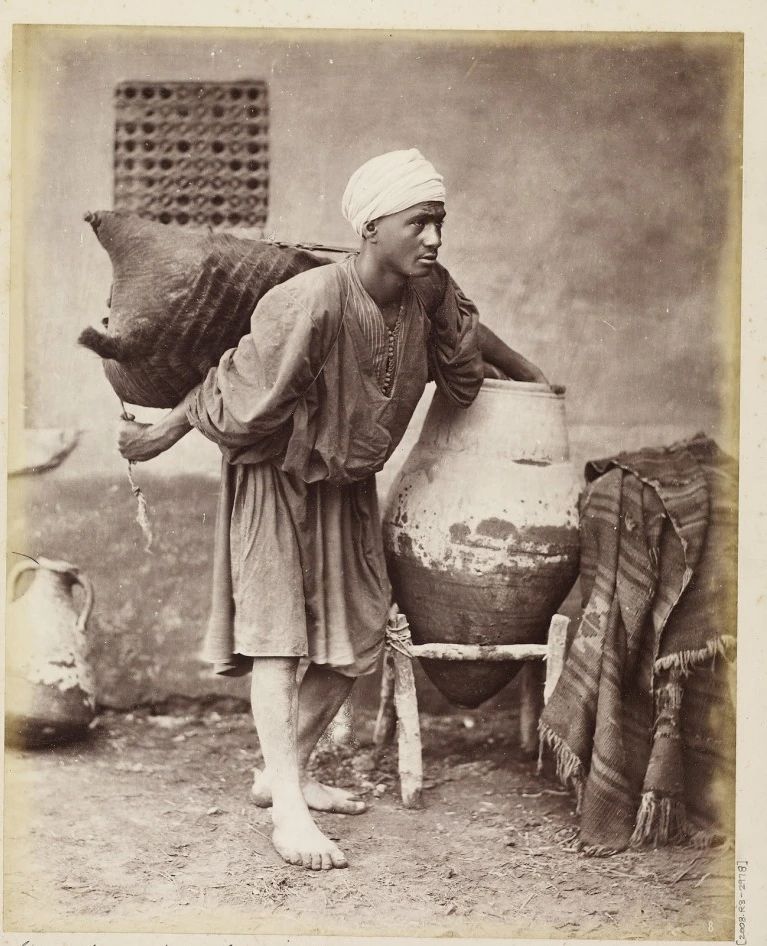

Among the early photographs that fascinated Thürlemann were those produced between 1865 and 1880, capturing the diverse population of Cairo engaged in their daily activities. For instance, there were images of the Sakkah, or water carriers, labouring barefoot to transport heavy loads of Nile water in goat skins to households, where it was filtered before use.

As Thürlemann delved deeper into these photographs, he noticed a recurring element—a latticed wooden screen known as the mashrabiyah. This traditional architectural feature was often depicted as an ornamental backdrop but occasionally played a crucial role in the image’s narrative.

The mashrabiyah was a characteristic element of the medieval quarters of Cairo, adorning houses like oriels. It served as a boundary for the inner circle of the family, including the pasha, his wives, children, and what was commonly known as the harem. These rooms were off-limits to male strangers, and the mashrabiyah acted like a one-way mirror, enabling women to observe life outside while remaining unseen. The screen also provided shade and allowed cool air to pass through, particularly in Egypt’s hot climate.

For foreign visitors to Cairo, these screens, with their exquisite craftsmanship and intricate patterns, were visually captivating but impenetrable to their gaze. Each screen obstructed their view and enticed their imagination. The tourists knew that behind these screens, authentic Egyptian family life.